Transformation Fundamentals – Five Key Things Needed for an Improvement Transformation to Succeed

There is a lot of dialogue around, on LinkedIn, in posts and books, as to why Lean and other Improvement Transformations fail. There are some fantastic books on this subject, in fact Bob Emiliani, has written a number of them that cover this topic far better than I ever could.

There is less information on how they succeed. There are a number of stories and books around that will inspire; 2 Second Lean and The Lean Turnaround to name but two of these. You can learn a lot from these books. However, because they are stories specific to a single company it can be hard to draw parallels between the success stories and our own reality.

Recently, I was asked to speak to a group of company owners and operational leaders when they visited for a ‘lean tour’. A ‘lean tour’ is when you go and check out someone else’s factory / company and hear their cool success stories and look around their place. On this occasion, the tour also included a classroom session where we were asked to talk about our own lean transformation.

To prepare for the talk, I did some thinking about the topic. What does make a successful transformation? I’ve been involved in improvement methodology and implementation for almost 25 years. In that time I’ve experienced some success and some failures when it came to transformation. A few years ago, after a similar networking event where again, I was asked to speak on this topic, I wrote down some of my earlier ideas. More time and more contemplation has allowed me to expand on this. I didn’t actually re-read this post until halfway through this new version. I’m gratified to see that past me and current me are in agreement. The only difference is that current me has now understood that there are couple more factors that make the whole thing pop. I’ve now also isolated these factors away from my own current situation and understood them more generically and universally.

I consider myself a perpetual student of improvement methodology and transformations. A veritable sponge, I’ve been soaking up all the good stuff for decades now. Each past, current and ‘new’ iteration of every methodology and thinking process related to systems and processes has been absorbed, considered, dissected, and cobbled together into my own emerging personal mental textbook. Over the years, as I’ve learned and grown I’ve studied methods, tools, culture, leadership, obstacles and barriers to change. I regularly bother people much cleverer than myself and pick their brains, adding this into the hybrid of knowledge swirling around in my overactive brain.

In 24 years, I’ve seen three proper examples of where a transformation in a system gained its own momentum. Each was different in their own way and its only the latest one that I consider to have the potential to have true longevity.

So why is that? What were the common factors that all systems had that allowed transformation to occur and grow organically? You may be surprised to find that these factors are related to but actually independent of any specific improvement methodology. You won’t find this theory in any Lean, Six Sigma or Theory of Constraints textbook. You also won’t find it in any ground breaking business book, although our Jim Collins “The Map” is probably the closest thing to it.

Factor One: Primordial Soup

A fundamental reason why the improvement transformation is successful is where everyone in the company is swimming in an improvement and innovation ‘primordial soup’

In all three cases, the leaders of the company were curious, adventurous and open minded. In a culture where ideas flourish, no matter how wacky, improvement is as natural as breathing. I had one manager who would rush into my workspace at least once a week with an amazing new idea or an epiphany. I now have one who is not really bothered by the concept of what is or isn’t possible. Another one introduced me to the works of the great Jim Collins and a concept that I will discuss later as a key factor in successful transformations.

If the base culture of a business is oozing with primordial improvement goodness, no matter how unstructured, this acts as system stem cells, able to be molded into whatever the organization needs to thrive.

Factor Two: Philosophy

While believe that success in improvement is independent of any specific methodology, that doesn’t mean that we can’t borrow or learn from the greats. My previous point was that inevitably, in order to have a successful transformation, these factors must be present. They are more like truths than guidelines. If you like, imagine a logical algorithm in the spirit of Goldratt’s Thinking Processes.

Logic: In order to have a successful improvement transformation, you must have a system where people can generate and implement improvement ideas encumbered and do so relentlessly and perpetually.

So this is where philosophy comes in. If we believe in the above logic and use it to underpin all of our thinking in relation to our forward strategy, our daily planning and our operations, we can’t help but create a system that transforms.

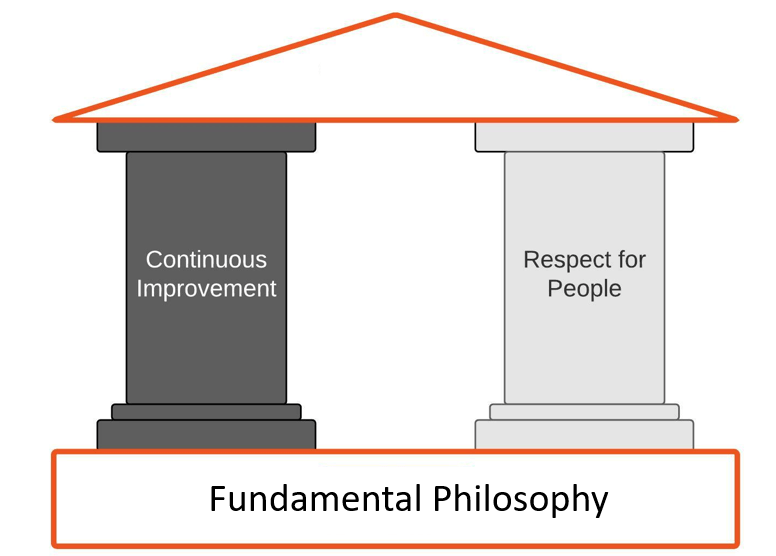

If you were to represent this visually, it might look a lot like a very familiar pair of pillars:

An organization’s interpretation of philosophy must ultimately belong to itself. I think that if we were to examine successful companies in the style of Jim Colins, we would however find a version of this philosophy in all of them.

Factor Three: Target Vision

If Factors One and Two are the embodiment of the famous quote by Peter Drucker “Culture eats strategy for breakfast” then Factor Three is more along the lines of, but everything just goes along faster if you all go in the same direction. Knowing what direction is in the first place is also a bonus.

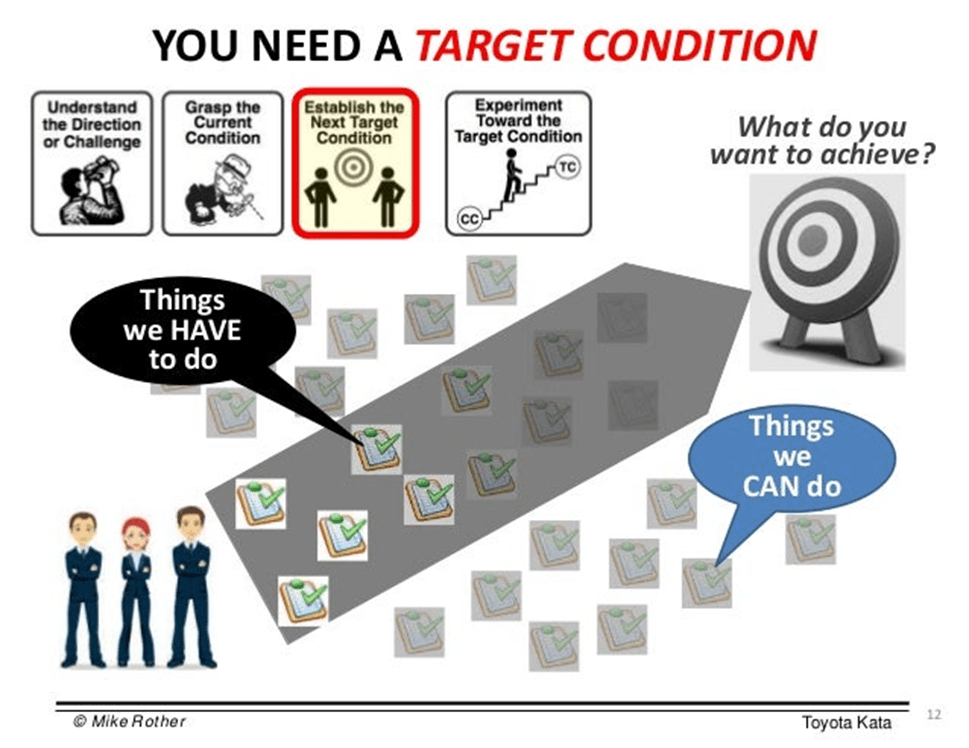

Again, in every ‘successful’ improvement and business methodology you will see similar practices. Whether it is called Hoshin Kanri, Hedgehog concept, Kata or whatever, its the same thing:

- Deeply understand what you are trying to achieve (big picture)

- Try to mostly do stuff that will send you in that direction

The best visual representation I’ve see of this, is by Mike Rother in a talk he did on the lessons learned from his book Toyota Kata.

Of course there are always many things we can do to improve, so many things need improvement right? There are however, things that we must do to move us towards our goal. Organizations that work on targeted improvement are more likely to transform in my opinion. This is simply because targeted improvement generates tangible results faster and that is a very good thing. The reasons why this is important is strongly tied to Factor Five to be discussed later.

Factor Four: Daily Improvement Culture

In my experience, reading and learning from people that study systems is an excellent way to form a hybrid methodology that takes from all but subscribes to only those concepts that are directly related and beneficial to your own unique process and environment.

A few years ago I was diligently studying the leadership culture of successful lean companies and specifically Toyota. While I knew that successful companies were practicing ‘daily improvement’, I didn’t really understand this at a level other than: more improvement = good.

Again, it was a key note speech by Mike Rother that made the methodology fireworks go off in my brain:

“If we only periodically conduct training events or only episodically work on improvement – and the rest of the time it’s business as usual – then according to neuroscience what we’re actually teaching is business as usual” – Mike Rother

Neuroscience! If we only do improvement infrequently, in kaizen events or projects, then our brains see these activities as ‘special’. After doing them, we return to doing ‘actual business.’ No wonder everyone sees improvement as a burden despite the fact that we all know it brings tangible rewards.

Side note: If your improvement program is not bringing tangible rewards, head back to Factor Three 😉

Personally, I already knew that practice and repetition of waste reduction activities would build momentum over time (Factor Five coming up soon I promise). Instinctively I knew this, but Rother’s work made this a tangible and scientific fact.

This ‘business as usual’ concept fascinated me. It changed my mindset around the frequency of improvement. When a leader asked me for advice on how to get his team to stop skipping their weekly improvement meetings due to ‘production issues’ or ‘being too busy’ I replied, “I suggest you do it every day then.” Why? Because, making it daily would make it a daily habit, not a weekly thing to forget. It’s a common phenomenon. I mean, it works the same with fortnightly meetings. You might be awesome at meeting on a project weekly but as soon as you make it fortnightly…..whoa….you start forgetting that it’s on, or you accidentally find yourself in the middle of something else and getting a phone call to say ‘where are you’? But I digress.

I knew from stories from other organizations that the more emphasis they put on daily improvement, the more benefits they saw and the more improvement they did. One startling example of this is Cambridge Engineering. They spend two hours per day on improvement. yes, that’s right, two hours per day. Don’t believe me? Check out this video and hear it from them. Is there a sweet spot for this? There must be. Of course, if we only do improvement and don’t actually produce anything the customer is willing to pay for well…we won’t last long. However, there is some merit to devoting a proportion of each day to only focusing on ways we can produce more effectively.

In every business there are millions of problems and issues that we would pay more attention to solving and removing, if we only had the time. In reality, there is never enough time. The only way forwards is to actually pause, and address the issue.

Today, I was involved in a discussion about an area of our own plant that is having problems. One of the issues is that no one in our team has time to do the detailed grunt work that would get us out of the ‘manure’. We know that it is a sure thing that our lives will improve if we do the work. We are not inexperienced improvement practitioners and yet, we hesitate to just get it done, because its hard, because we might fail, because we might lose production if we change our focus. My observation here is that production managers (and probably all other managers responsible for the doing of stuff) think that success is directly and only related to what is produced.

What our team learned during the crazy demand of the pandemic years was that:

When you can only focus on production and fail to maintain systems, your systems degrade and you end up inevitably with less production. As managers, our role in a system is to develop, maintain and improve that system perpetually towards the target vision. If this is done diligently, production will automatically fall out of this system at the desired rate.

What is the best way to ensure that systems are developed, maintained and improved diligently? Develop a culture of constant and consistent focus on improvement. Do it every day maybe?

Factor Five: Flywheel Concept

And so at last we come to the enigmatic Factor Five. The Flywheel Concept.

Consistent readers of this blog will know that I am a massive fangirl of Jim Collins and in particular, the Flywheel effect. Both in personal and business strategic success, this concept is a key factor.

Collin’s concept of the Flywheel effect can be summarized very briefly. In short, it is a series of repeating steps that when implemented consistently and relentlessly create a cycle of momentum that slowly but steadily moves a company, organization or person towards greatness.

In short,

FIGURE 1: MY ADAPTATION OF THE FLYWHEEL EFFECT DIAGRAM IN GOOD TO GREAT BY JIM COLLINS

In Good to Great, Collins discovered that in all the ‘great’ companies there has been “no miracle moment.” On the outside, companies seemed to “breakthrough” but in reality there was a “quiet, deliberate process of figuring out what needed to be done to create the best future results and then simply taking those steps, one after the other, turn by turn of the flywheel.”

My current theory on the failure of transformations that had some or all of the previously discussed factors but still failed is tightly linked to the Flywheel effect. I surmise that many organizations that give up on their lean or improvement journey due to ‘lack of progress’ were probably on the verge of astronomical success right before they quit. They were pushing the flywheel but due to perceived lack of progress, grew discouraged and stopped pushing.

This phenomena is well described by James Clear in his book Atomic Habits. He calls this ‘the Valley of Disappointment.’ He suggests that our expectation for progress is linear, when in reality there is a whole period of time where we only build latent potential and do not see results. This can be a period of deep disappointment and don’t.

My experiences have shown that this idea is more likely than not to be true. In Jim Collins has also described this effect but in terms of a flywheel. The seemingly exponential results achieved by ‘great’ companies come at the end of the ‘valley of disappointment’ when latent potential is finally realised.

Long story short, companies that succeed in any successful transformation have travelled through the valley of disappointment, of low results, of negligible progress and have done one very important thing. They just kept pushing the Flywheel no matter what.

It is a certainty that any improvement transformation will fail if we no longer continue to implement it. However, if we continue to persevere, we cannot help but see some kind of progress. Where companies grow discouraged is in the expectation of ‘what success looks like’ and ‘when we will see results.’

In my experience, momentum becomes visible at around the four year mark. Four years. Before this, success is seen in sporadic success and is highly reliant on strong, dedicated leadership and infinite patience.

So, to succeed with Factor Five is easy. Just don’t quit.

Conclusion: Success is Independent of Methodology

Despite the fact that this blog post and much of my work is based around the improvement methodology that is right or wrongly called ‘lean’, what I have learned about improvement transformations is that they have very little to do with methodology.

The first successful one I was involved in was heavily based in the work of Goldratt and the Theory of Constraints. The second one was very Toyota Production System/lean. And the most recent one has evolved beyond any of these. The solutions and methodologies we are using are uniquely and appropriately our own, drawing from years of trying and sponging and learning and growing.

Transformation moves like a Flywheel and the sophistication of the system peels like an onion.

I have always been a strong advocate that improvement is at the fingertips of anyone that wants it. The purpose of this post was to summarize twenty plus years of hands on learning and make it available to others with the hope that it brings them confidence and lessens the feeling of overwhelm that so many people experience when wanting to improve. So I’ll end this post with one simple piece of advice.

If you want to improve, just start and don’t stop.